Baseball game in Beachville, Ontario, 1838

As recalled by Dr. Adam E. Ford, in the May 5, 1886 issue of Sporting Life.

A Game of Long-ago Which Closely Resembled Our Present National Game.

Denver, Col., April 26. Editor Sporting Life.

The 4th of June, 1838 was a holiday in Canada, for the Rebellion of 1837 had been closed by the victory of the government over the rebels, and the birthday of His Majesty George the Fourth was set apart for general rejoicing. The chief event at the village of Beachville in the County of Oxford, was a baseball match between the Beachville Club and the Zorras, a club hailing from the township of Zorra and North Oxford.

The game was played in a nice smooth pasture field just back of Enoch Burdick’s shops; I well remember a company of Scotch volunteers from Zorra halting as they passed the grounds to take a look at the game. I remember seeing Geo. Burdick, Reuben Martin, Adam Karn, Wm. Hutchinson, I. Van Alstine, and, I think, Peter Karn and some others. I remember also that there were in the Zorras “Old Ned’ Dolson, Nathaniel NcNames, Abel and John Williams, Harry and Daniel Karn, and, I think, Wm. Ford and William Dodge. Were it not for taking up too much of your valuable space I could give you the names of many others who were there and incidents to confirm the accuracy of the day and the game. The ball was made of double and twisted woolen yarn, a little smaller than the regulation ball of today and covered with good honest calf skin, sewed with waxed ends by Edward McNames, a shoemaker.

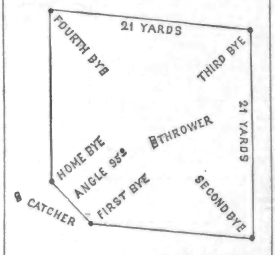

The infield was a square, the base lines of which were twenty-four yards long, on which were placed five bags, thus [see Figure 3].

The distance from the thrower to the catcher was eighteen yards; the catcher standing three yards behind the home bye. From the home bye, or “knocker’s” stone, to the first bye was six yards. The club (we had bats in cricket but we never used bats in playing base ball) was generally made of the best cedar, blocked out with an ax and finished on a shaving horse with a drawing knife. A Wagon spoke, or any nice straight stick would do.

We had fair and unfair balls. A fair ball was one thrown to the knocker at any height between the bend of his knee and the top of his head, near enough to him to be fairly within reach. All others were unfair. The strategic points for the thrower to aim at was to get near his elbow or between his club and his ear. When a man struck at a ball it was a strike, and if a man struck at the ball three times and missed it he was out if the ball was caught every time either on the fly or on the first bound. If he struck at the ball and it was not so caught by the catcher that strike did not count. If a struck ball went anywhere within lines drawn straight back between home and the fourth bye, and between home and the first bye extended into the field the striker had to run. If it went outside of that he could not, and every man on the byes must stay where he was until the ball was in the thrower’s hands. Instead of calling foul the call was “no hit.”

There was no rule to compel a man to strike at the ball except the rule of honor, but a man would be despised and guyed unmercifully if he would not hit at a[. . .] fair ball [. . .] he was out if the ball was caught either before it struck the ground or on the first bound. Every struck ball that went within the lines mentioned above was a fair hit, every one outside of them no hit, and what you now call a foul tip was called a tick. A tick and a catch will always fetch was the rule given strikers out on foul tips. The same rule applies to forced runs that we have now. The bases were the lines between the byes and a base runner was out if hit by the ball when he was off of his bye. Three men out and the side out. And both sides out constituted a complete inning. The number of innings to be played was always a matter of agreement, but it was generally 6 to 9 innings, 7 being most frequently played and when no number was agreed upon seven was supposed to be the number. The old plan which Silas Williams and Ned Dolson (these were greyheaded men then) said was the only right way to play ball, for it was the way they used to play when they were boys, was to play away until one side made 18, or 21, and the team getting that number first won the game. A tally, of course, was a run. The tallies were always kept by cutting notches on the edge of a stick when the base runners came in. There was no set number of men to be played on each side, but the sides must be equal. The number of men on each side was a matter of agreement when the match was made. I have frequently seen games played with seven men on each side, and I never saw more than 12. They all fetched.

The object in having the first bye so near the home was to get runners on the base lines, so as to have the fun of putting them out or enjoying the mistakes of the fielders when some fleet footed fellow would dodge the ball and come in home. When I got older, I played myself, for the game never died out. I well remember when some fellows down at or near New York got up the game of base ball that had a “pitcher” and “[. . .] ‘s” etc., and was played with a ball hard as a stick. India rubber had come into use, and they put so much into the balls to make them lively that when the ball was tossed to you like a girl playing “one old-cat” you could knock it so far that the fielders would be chasing it yet, like dogs hunting sheep, after you had gone clear around and scored your tally. Neil McTaggert, Henry Cruttenden, Gordon Cook, Henry Taylor, James Piper, Almon Burch, Wm. Harrington and others told me of it when I came home from university. We, with “alot of good fellows more” went out and played it one day. The next day we felt as if we had been on an overland trip to the moon. I could give you pages of incidentals but space forbids. One word as to the prowess in those early days. I heard Silas Williams tell Jonathan Thornton that old Ned Dolson could catch the ball right away from the front of the club if you didn’t keep him back so far that he couldn’t reach it. I have played from that day to this and I don’t intend to quit as long as there is another boy on the ground.

Yours, Dr. Ford